ENERGY AGGREGATION AND ENERGY QUALITY

Aggregation of primary-level economic data has received substantial attention from economists for a number of reasons. Aggregating the vast number of inputs and outputs in the economy makes it easier for analysts to discern patterns in the data. Some aggregate quantities are of theoretical interest in macroeconomics. Measurement of productivity, for example, requires a method to aggregate goods produced and factors of production that have diverse and distinct qualities. For example, the post-World War II shift toward a more educated workforce and from nonresidential structures to producers’ durable equipment requires adjustments to methods used to measure labor hours and capital inputs. Econometric and other forms of quantitative analysis may restrict the number of variables that can be considered in a specific application, again requiring aggregation. Many indexes are possible, so economists have focused on the implicit assumptions made by the choice of an index in regard to returns to scale, substitutability, and other factors. These general considerations also apply to energy.

The simplest form of aggregation, assuming that each variable is in the same units, is to add up the individual variables according to their thermal equivalents (Btus, joules, etc.). Equation (1) illustrates this approach:

N

Et = E Eit, (1)

i=1

where E is the thermal equivalent of fuel i (N types) at time t. The advantages of the thermal equivalent approach are that it uses a simple and well-defined accounting system based on the conservation of energy and the fact that thermal equivalents are easily measured. This approach underlies most methods of energy aggregation in economics and ecology, such as trophic dynamics national energy accounting, energy input-output modeling in economies and ecosystems, most analyses of the energy/ gross domestic product (GDP) relationship and energy efficiency, and most net energy analyses.

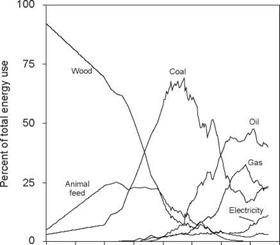

Despite its widespread use, aggregating different energy types by their heat units embodies a serious flaw: It ignores qualitative differences among energy vectors. We define energy quality as the relative economic usefulness per heat equivalent unit of different fuels and electricity. Given that the composition of energy use changes significantly over time (Fig. 1), it is reasonable to assume that energy quality has been an important economic driving force. The quality of electricity has received considerable attention in terms of its effect on the productivity of labor and capital and on the quantity of energy required to produce a unit of GDP. Less attention has been paid to the quality of other fuels, and few studies use a quality-weighting scheme in empirical analysis of energy use.

The concept of energy quality needs to be distinguished from that of resource quality. Petroleum and coal deposits may be identified as high - quality energy sources because they provide a very high energy surplus relative to the amount of energy required to extract the fuel. On the other hand, some forms of solar electricity may be characterized as a

|

1800 1825 1850 1875 1900 1925 1950 1975 2000 FIGURE 1 Composition of primary energy use in the United States. Electricity includes only primary sources (hydropower, nuclear, geothermal, and solar). |

low-quality source because they have a lower energy return on investment (EROI). However, the latter energy vector may have higher energy quality because it can be used to generate more useful economic work than one heat unit of petroleum or coal.

Taking energy quality into account in energy aggregation requires more advanced forms of aggregation. Some of these forms are based on concepts developed in the energy analysis literature, such as exergy or emergy analysis. These methods take the following form:

N

e; = J2 itEit, (2)

i=1

where l represents quality factors that may vary among fuels and over time for individual fuels. In the most general case that we consider, an aggregate index can be represented as

N

f (Et )=E Itg(Eit), (3)

i=l

where f() and g() are functions, 1it are weights, the Ег - are the N different energy vectors, and Et is the aggregate energy index in period t. An example of this type of indexing is the discrete Divisia index or Tornquist-Theil index described later.