HEALTHY ITERATION DRIVES LEARNING

Eric Ries, a software engineer and entrepreneur who launched his Lessons Learned blog in 2008 and quickly became a leading champion of “lean startup” principles for dealing with the pervasive uncertainty faced by new ventures, often opens his startup workshops with a pair of absurd videos.4 The first features a confident Ali G (one of comedian Sacha Baron Cohen’s fictional alter egos) pitching a product idea called the “Ice Cream Glove” to investors, including Donald Trump and a series of unwitting venture capital pros. The Ice Cream Glove is a rubber glove that Ali G claims will take the world by storm, because it allows people to eat ice cream cones without getting ice cream on their hands. Later in the video, he unveils his “hover - board,” basically a skateboard without wheels, which he hopes will be converted, thanks to venture capital funding, into a flying platform. These ideas are so comical that the most priceless aspects of the footage are Ali G’s sincerity in pitching his concepts and the dumbfounded looks on his listeners’ faces.

Ries’s second video is an infomercial for the Snuggie, the “blanket with sleeves” that served as the butt of many jokes in late 2008 and 2009. The Snuggie-clad characters in the ad are hard to watch without guffawing, which is why so many first-time viewers of the ad thought it was a fictional spoof. But the Snuggie was no joke from a revenue and marketing standpoint. It sold more than 4 million units in its first few months and caught fire as a pop culture phenomenon, leading USA Today to proclaim in January of 2009, “The Cult of Snuggie threatens to take over America!”5

Ries says that when he first saw the Snuggie ad, he found the idea so laughable that he was sure it was a hoax or a joke, just like the Ice Cream Glove. His point in sharing these videos is that you cannot know in advance how the market will react to your new product or service. “Most entrepreneurs, when they are pitching their products to investors, to potential partners, and even to future employees,” he writes, “sound just like Ali G pitching the Ice Cream Glove: in love with their own thinking, the amazing product features they are going to build—and utterly out of touch with reality.”6 Your best plans, predictions, and upfront analyses are meaningless unless, and until, they are validated by customer behavior.

Wernher von Braun, the famous NASA rocket scientist, said “one test result is worth one thousand expert opinions,” a principle that applies perfectly to the startup journey. “You cannot figure out what products create value for customers at the whiteboard,” Eric Ries writes, “where all you have to draw on are opinions.” To avoid sinking all of your resources into a nonviable idea, Ries urges new entrepreneurs to get “out of the building” as early as possible and expose their concept to actual customers, to the fact-based scrutiny of the marketplace.7

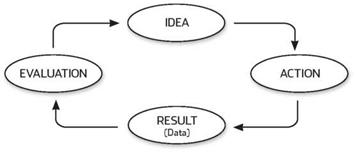

Iteration is an indispensable tool for putting your startup on a discovery-driven track. As shown in Figure 6-2, the basic cycle of iteration is not hard to grasp. An idea leads to action, which leads to a result that can be evaluated. You try something; you observe or measure the outcome; and you develop a new and improved idea to carry into the next iteration. This cycle will look familiar to those with experience in the continuous improvement or lean production movements (echoing the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle and similar frameworks).

|

Figure 6-2. The basic cycle of iteration.

|

Note that the iteration cycle echoes the core pattern of the passion trap, as described in Chapter Two, providing clues as to why highly enthusiastic founders often fail to effectively iterate. First, founders fall in love with their original idea and strive to perfect it, putting most of their resources into the idea step. “We know this is a great idea,” the thinking goes, “Why do we need a trial or a proof-of-concept? Let’s put smart people and plenty of money behind it, design it just right, and go to market with a bang.”

Second, if iteration does occur, the founding team’s commitment to their solution can lead to a weak evaluation step in which founders show little interest in unedited customer feedback and deny or rationalize negative feedback received. For these reasons, a vital distinction exists between superficial iteration, going through the motions with little to show for it, and healthy iteration, which is like the shedding of a skin. Dead ideas and unworkable strategies are cast aside to make way for the stronger core. As Ries observes, “within every bad idea is a kernel of truth.”8 Successful iteration discovers this truth.