Developing a Strong Market Orientation

Of all the factors that can help you get your business off the ground, the most important will be the presence of a ready market, which can be defined as a sufficient number of actual (versus potential) customers who will pay, right now, for a product or service. There is no room for abstraction on this simple point. Truly superior business concepts always translate into living, breathing customers who will pull out their wallets and hand over hard-earned money. Everything else is a warm-up.

This is why hard work, cool technology, lots of funding, or superior talent won’t, by themselves, guarantee startup success. In fact, if the market is right, these attributes might not even be necessary. A founder with questionable skills, little money, and a B-grade product might still launch a business by stumbling into a white-hot market, which can disguise and cure a lot of ills. When J. C. Faulkner built D1 into one of the strongest mortgage companies in the United States, during the late 1990s, he knew that some of his competitors made money only because of a booming market. “When running downhill,” he would say, “everybody thinks they’re an athlete.” He wanted his team to be ready for the inevitable market downswing, and when it came, D1 swiftly outran its competitors.

As a passionate founder, you must wrestle with a paradox. Passion is an inner force, driving you from the inside out. But the surest way to get a new venture off the ground is to build it from the outside in, allowing market forces to pull and shape your idea into a thriving business. As we saw in Chapter Two, your attachment to a cool business concept can amplify your inner world of belief and optimism so much that you lose your objectivity about the needs, desires, and fears of prospective customers and move forward with a product that nobody wants.

The best possible antidote is to bring a strong market orientation to your new venture. A market orientation will immunize you against one of the most dangerous effects of the passion trap: your blind faith that customers will believe in your product simply because you do. And although it won’t guarantee that you’ll immediately find the perfect market for your idea, a healthy market orientation will dramatically improve your odds of finding a ready base of customers to sustain your startup.

What is a market orientation? I’ve found that market-oriented entrepreneurs do three things to ensure that their passion connects with ample opportunity:

1. They obsessively emphasize the market and the customer. This is a mindset issue. How do you think about your business relative to the customers you serve? Are you determined to build your business from the outside in? Are you starting with the market:, and developing your business from there, or are you a "product in search of a market”?

2. They strive to know their markets and customers. How fully do you understand your customers, their needs and preferences, and the problems you are solving for them? How will you continue to improve your knowledge over time?

3. They execute on the market opportunity. How will you successfully market and sell your offerings? What kind of sales engine is required for success? Do you really understand how customers experience your products and services, and what kind of value is created for them?

Through the rest of this chapter, I will further define these three strategies to ensure that you find and connect with customers who are just as passionate about your offerings as you are. Then, I’ll share a set of questions for giving your startup idea a market scrub to scrutinize your concept in the bright light of the marketplace.

The next time you’re in line at a fast food-restaurant or a corner drugstore, pay attention to the transaction happening in front of you. Do you see a product being sold or a human need being met? Do you see a hamburger or hunger? A bottle of Ibuprofen or a spouse at home with a killer headache?

How you see the world of commerce will govern how you design, build, and run your startup. Whether you see the world as products or as needs is vitally important. We live in an increasingly consumer - and technology-driven culture, and we love stuff: gadgets, widgets, technologies, and things. Most of us, most of the time, “see” products and services when we look at a business.

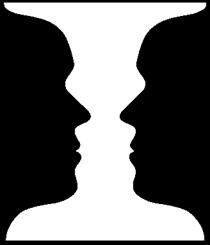

But every successful offering corresponds to a need it was designed to meet. Products and needs are inseparable. To continually remind myself of this, I keep a shabby hand-drawn rendering of the classic figure-ground illusion (see Figure 4-1) taped to my office wall.

|

Figure 4-1. The figure-ground illusion.

|

In the picture, I see the white vase as my product or service. It represents my great idea, my “baby.” Of course, as I continue looking, foreground and background will shift, revealing two faces in profile.

These are the faces of the customers who shape my product, the markets that give life to any business. Whether I notice them or not, they are always there.

Emphasizing your market means continually seeing the faces, never losing sight of the market’s absolute power over your business, despite force of habit drawing your attention back to the vase, again and again. Focus on your market, the wellspring of any healthy business, and you can be confident that the right products and services will emerge over time.

Stacy’s Pita Chips would never have been born if its founders had clung to their original business idea or if they had overlooked an unexpected market need standing, literally, right in front of them. In the mid-1990s, Stacy Madison, a Boston social worker, dreamed of opening a health food restaurant. With very little money, she and her business partner, Mark Andrus, decided to start with a small sandwich cart in downtown Boston, selling all-natural pita-wrap sandwiches. Hungry customers were soon forming long lines down the block. To keep them interested while they waited, Stacy and Mark served them seasoned pita chips baked from leftover pita bread. Customers flipped over the chips, convincing Stacy and Mark to package them for sale in stores. Before long, the retail chip business took off, so they abandoned their restaurant plans and pursued the pita chip idea full-time. In 2006, having achieved more than $60 million in annual sales, Stacy’s Pita Chips was acquired by Frito-Lay, the world’s largest snack food company. Not bad for a lunch-cart business, and all possible because Stacy and Mark put their attention where it belonged, on a customer need.5

The idea of placing emphasis on market needs is hardly revolutionary, but it is easier said than done, especially among technologists and product developers. Paul Graham knows this as well as anyone. Through Y Combinator, his seed-stage technology venture fund, he invites a wide array of ideas from very young, mostly brilliant software engineers, hoping to launch the next Google or Facebook. Graham says that a lot of funding requests come from “promising people with unpromising ideas,” so he and his colleagues have settled on a four - word mantra for what makes a technology stick: Make something people want. It permeates every Y Combinator program and is printed on Tshirts given to startup teams. “If you had to reduce the recipe for a successful startup to four words,” Graham says, “those would probably be the four.”6