Limited Liability Company and Limited Partnership Equity

As you may recall, limited liability companies (LLCs) and limited partnerships (LPs) are pass-through tax entities. This means that they file tax returns but do not pay any income tax. Instead, the net income and losses of the company flows through to the equity holders (members or limited partners) and is reported on their individual tax returns.

Partnership (pass-through entities) tax law is complex, so check with your attorney and accountant every step along the way.

To understand how a pass-through tax entity works, it is helpful to define certain terms. The first term is allocation. Net income and losses of passthrough tax entities are allocated among the equity holders in predetermined percentages. Those percentages can correspond directly with the percentage of ownership of the company or they could be different. The latter is called a special allocation that can be used to accelerate an investment return to investors. The second term is distribution. After the net profits and losses have been allocated to the equity holders, some or all of the net profits can be distributed to them.

The difference between allocation and distribution is important because an equity holder will pay taxes at the end of the year based upon the amount of net income allocated to them and not on the amount that is actually distributed to them. All operating agreements and limited partnership agreements should have a provision allowing the managers to distribute sufficient monies to pay the taxes on all allocated but undistributed sums for a particular tax year.

A number of factors determine how much of the net profits that have been allocated to the equity holders will actually be distributed. The most important factor is the need to retain funds for use in the operation and expansion of the business. A company may need to retain a portion of the net profits and use them for the operation of the business rather than to raise more capital from new investors. The basic point, however, is that net profits do get distributed eventually. This is a big advantage over a corporation in which common stockholders may have to wait years before seeing any return on their investment. For this reason alone, pass-through tax entities are an attractive investment vehicle.

The complex partnership tax laws that underlie LLCs and LPs allow for a greater amount of flexibility when it comes to creating an attractive return for investors. The company can allocate a disproportionate amount of the net income or loss to investors. For example, investors may only hold 10% of the equity, but they could be allocated 50% of the net profits to create an accelerated return on their investment.

While LLCs and LPs are treated the same for tax purposes, there are differences in the way each is structured and the way in which equity is offered to investors.

Limited Liability Company Equity

The equity of a limited liability company (LLC) is called a membership unit (or interest). Unlike a limited partnership, every member of an LLC may participate fully in the management of the company. When an LLC is formed, it may elect to be managed by a manager or managers or by the members themselves. As a practical matter, if an LLC is looking to

Raise capital from investors, it will more than likely be run by a manager or group of managers.

Limited liability companies are ideally suited for businesses that are looking to focus on the delivery of a few products or services that will produce distributable cash. Also, keep in mind that an LLC can convert to a corporation in a tax-free exchange known as a Section 351 exchange if the needs of the company change in the future.

An LLC is different than a corporation because it does not have to state a maximum amount of membership units. There can be an infinite number of membership units. However, as part of the planning process to make an LLC attractive to investors, the managers of the LLC will often define a maximum amount of membership units that the LLC can issue in the operating agreement.

A number of factors need to be taken into account when deciding the maximum number of membership units in an LLC, including the total amount of money that the company anticipates raising from investors and the valuation of the company.

/ Figure 3.2: AN LLC EXAMPLE

Three people meet through a local business networking event. One is a designer of custom jewelry, the second has experience in managing a company, and the third has marketing experience. The three decide to pool their talents to create a line of custom jewelry and market it to wholesale jewelry dealers.

After meeting with an attorney, the three decide to form an LLC in which they will serve as managers. Each person will have an equal amount of decision-making responsibility and equal amounts of membership units in the company. After filing Articles of Organization with the state corporation commission, they work with their attorney to draft an Operating Agreement for the company.

As part of the Operating Agreement, they designate different classes of membership units to be divided among the founders, investors, and principals of the company (managers, officers, directors, employees, and consultants). The different classes of membership units will have vastly differ-

Ent attributes. The class reserved for the founders will have voting rights, while the class to be issued to the investors and principals of the company may not. In addition, the allocation of net income will be weighted heavily in favor of the investors at first and then gradually even out over time.

The managers then work with their attorney, accountant, and a business plan writer to draft a business plan and financial projections. The cost estimate for designing, manufacturing, and marketing the jewelry comes in at $350,000. Based on a number of factors, the company can justify a valuation of $1,000,000. Therefore, if the company were to set a maximum limit of 10,000,000 membership units and then sell 3,500,000 membership units at $0.10 per unit, it would raise enough capital to achieve its goals.

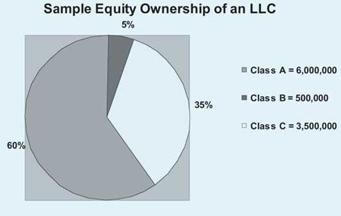

The membership units will be split up into three classes:

• 6,000,000 Class A membership units will be reserved for issuance to founders and managers;

• 500,000 Class B membership units will be reserved for issuance to officers, directors, employees, and consultants; and,

• 3,500,000 Class C membership units will be reserved for issuance to investors.

Obviously, the Class A membership units would be issued to the founders first. Over time, some Class B membership units would be issued as incentives (much like stock options in a corporation) to officers, directors, employees, and consultants. Class C membership units would be sold to investors.

|

A sample breakdown of the three classes of membership units would probably look like this:

|

Holding 60% or 6,000,000 of the 10,000,000 maximum authorized membership units will ensure that the founders retain decision-making control over the company for quite some time. Issuing up to 5% or 500,000 membership units as incentives will help establish the culture that the officers, directors, employees, and consultants are valuable members of the team and provide incentive for them to do a good job. Setting aside 35% or 3,500,000 will ensure that the company has enough breathing room to be able to raise the additional capital it will need to set up and expand its operations.

Most often, an LLC will structure a graduated reduction in the percentage of net profits allocated to investors. For example, even though the investors as a group will only own 35% of the equity, they could be allocated 60-80% of the net profits until they have been allocated an amount equal to their investment in the company. Thereafter, the investors could be allocated an amount that corresponds directly with their percentage of ownership of the company. There are obviously innumerable variations on this theme that will most likely be driven by how fast investors expect a return on their investment and how large those returns should be.

The equity of a limited partnership is called a limited partnership interest. Limited partnership interests are typically designed and marketed to passive investors whose monetary returns are dependent upon the efforts of the general partner. Most investors in limited partnerships invest because of the passive nature of the investment. They neither want nor desire to make decisions for the partnership. In fact, unlike an LLC, if a limited partner takes too much control of the operation of the business, they run the risk of incurring personal liability just like a general partner.

The Revised Uniform Limited Partnership Act, which has been adopted by a majority of states, lists a number of activities that a limited partner can engage in without triggering personal liability. Some of those activities include:

• being an officer, director, or shareholder of a corporate general partner;

• consulting with or advising the general partner on business matters;

• voting on dissolution of the partnership;

• voting on the sale or mortgaging of partnership assets;

• voting on the incurrence of unusual indebtedness;

• voting on the admission or removal of general or limited partners;

• voting on transactions involving potential conflicts of interest; and,

• all other matters required by the partnership agreement.

Limited partnerships are well-suited for investment ventures that are looking for a handful of high net worth investors, like real estate investments. The general partner will solicit the interest of a few investors, form the limited partnership, and have the limited partnership agreement drafted. The investors will then be brought on board by signing the limited partnership agreement and contributing capital to the venture.

Just like LLCs, limited partnerships do not have to state a maximum amount of authorized capital. The limited partnership agreement usually limits the number of limited partnership interests to be sold to investors.

Typically, the net income and losses of a limited partnership will be split between the general partner and limited partners, with a disproportionate amount being attributed to the limited partners at the beginning and leveling out later on.

Allocation of the net income and losses of the limited partnership are typically split between the general partner and limited partners. In the scenario, the three founders formed a corporation that served as the general partner and they also contributed capital as limited partners. However, a general partner is under no obligation to contribute any capital to the venture.

Because the three founders are serving as officers of the corporation, which is the general partner, they will be entitled to receive compensation from the share that is allocated to the general partner. Because they also hold 200,000 limited partnership interests, they will be entitled to their percentage of the share that is allocated to the limited partners.

The three founders will not run into trouble and risk incurring personal liability, because they are allowed, as officers and directors of corporation that serves as the general partner, to have decision-making power.

Figure 3.3: THE LP EXAMPLE

Three people are interested in purchasing a piece of commercial real estate for investment, but they do not have enough cash to obtain financing. After consulting with an attorney, they decide to form a limited partnership. The three of them intend to share equally in the decision-making power for the limited partnership, but are concerned about being personally liable for the debts and obligations of the limited partnership. Therefore, the three of them form a corporation in which they are the directors and officers, and appoint that new corporation as the general partner of the limited partnership.

After filing a Certificate of Limited Partnership with the state corporation commission, they work with their attorney to draft a Limited Partnership Agreement. The three of them together contribute $200,000 to the venture. In order to obtain financing, they calculate that they will need to raise an additional $800,000 from the sale of limited partnership interests.

The Limited Partnership Agreement sets the maximum amount of limited partnership to be sold at 1,000,000 and issues the first 200,000 limited partnership interests to the three founders who contributed the first $200,000. The limited partnership then works with their attorney to draft a Private Placement Memorandum to offer $800,000 in limited partnership interests under Rule 506. (see Chapter 5.) The limited partnership interests are offered to investors at $1.00 per unit of interest, with a minimum purchase of $50,000. Sixteen investors later, the limited partnership has the capital it needs to obtain its financing.

Just like an LLC, the limited partnership can allocate the net income and losses of the partnership any way it wants to. Typically, since the limited partners are putting up all of the capital, they will receive the lion's share of the profits and losses initially. After some time, the allocations can be adjusted.

QUICK Tip

Protect Yourself with Redundancy: Spell out your allocation amounts and schedule in both the limited partnership agreement and the private placement memorandum.

If the limited partnership was going to acquire multiple properties with the same financing, serious thought might be given to raising its capital through a series of offerings.